Tech industry’s critical policy issues likely tabled as Congress heads for recess

Congress is about to head out for summer recess with one major piece of tech policy legislation checked off but several others still hanging in the balance.

Lawmakers managed to pass more than $50 billion in funding toward domestic computer chip manufacturing, even after the initial vehicle for the bill was held up by negotiations around other issues.

But members will also head home without having voted on the most promising tech antitrust bill that’s advanced in both chambers and with talks around digital privacy legislation still in a precarious position.

The Senate has also yet to vote on whether to confirm President Joe Biden’s final nominee to the Federal Communications Commission, leaving the agency without a full panel for well over a year and a half. That also means the agency has not been able to reinstate net neutrality rules that would reclassify internet service providers as common carriers, an action many expected a Democratic administration to take once the agency was in full force.

After the August recess, lawmakers will be solidly in midterm mode with consequential campaigns threatening to transform the makeup of both chambers in the November elections. After that, Congress will have limited time in the final weeks of the year to pass any last-minute legislation before the committee gavels change hands, should Republicans win back control of either chamber.

“Sometimes the lame duck can be very productive,” said Harold Feld, senior vice president of the nonprofit Public Knowledge, which receives funding from both Big Tech and telecom companies as well as their detractors. But to have a productive session, he added, Congress must set promising measures up for success before the midterms.

Advocates say passing tech policy regulation is necessary to enable future innovation.

“I think if the U.S. doesn’t move forward on Big Tech regulations, what that is saying to Big Tech is that they’re untouchable,” said Andy Yen, CEO of Proton, which makes the encrypted email app Proton Mail and has spoken out against the tech giants. “So the abuses that we see today are only going to get worse.”

Here’s where things stand on tech policy heading into the August recess.

Semiconductor funding

Congress’ major accomplishment in tech policy this year has been in passing the Chips and Science Act, the computer chip funding bill that will support the development of semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S.

The funding is aimed at reducing U.S. dependence on foreign manufacturing, which leaves the country at risk for greater supply chain issues and economic crises, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has warned.

Semiconductor shortages during the pandemic have led to supply problems in devices that rely on them, including cars.

The chip manufacturing funding was initially part of a larger legislative package but was held up by negotiations over a separate issue. Lawmakers ended up peeling out the chips funding into a separate bill that both chambers passed and sent to the president’s desk.

“I think Congress just took seriously the message from semiconductor CEOs about the urgency of now,” said Paul Gallant, managing director of Cowen’s Washington Research Group. “The urgency of allocating this money now versus six months from now. Because companies have money being offered by Europe and Asia. So the U.S. either steps up to the table now or probably loses fabs to other countries.”

“The production of semiconductor chips is much more well understood and coveted now post pandemic,” said Linda Moore, CEO of tech industry group TechNet, pointing to supply chain challenges that have persisted throughout the crisis and impacted the availability of consumer products. “I think that people understand now that it’s really an economic security and national security issue to not have that kind of production here in our country.”

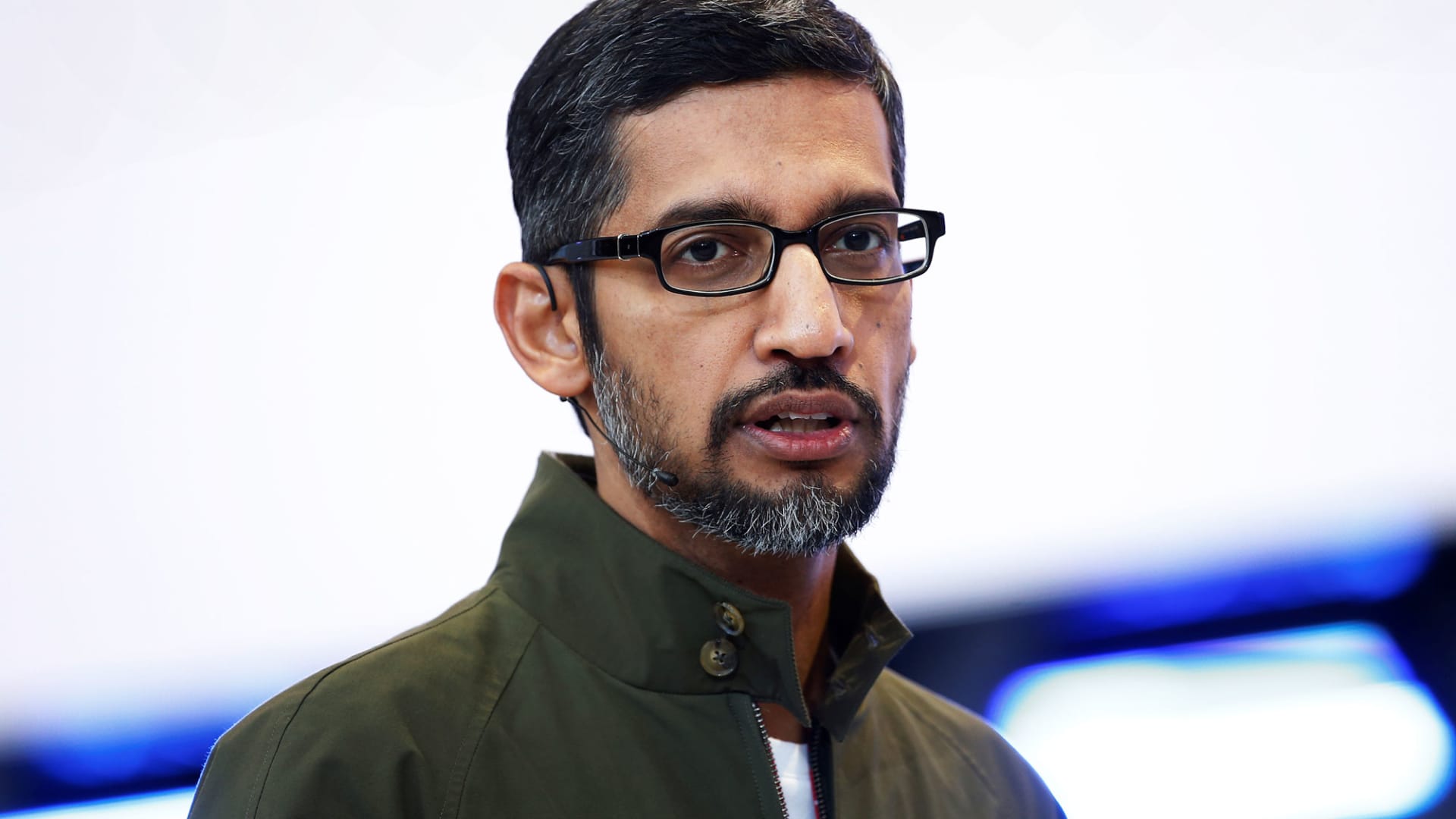

Antitrust

As of a couple of months ago, Congress seemed poised to actually take a vote on one of the most promising tech antitrust bills that advanced out of committee in both chambers, the American Innovation and Choice Online Act. But just last weekend, the bill’s lead sponsor, Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., admitted she no longer expected it to get a vote before the summer recess.

That significantly narrows the window of time lawmakers could have to pass the bill and gives tech lobbyists more time to sow doubts in members’ minds.

“It’s not like it’s going to die if it doesn’t get voted on in August, but you have to ask what’s going to change?” said Public Knowledge’s Feld.

Several people interviewed for this article who support the bill’s passage believe Schumer’s failure to schedule a vote on the bill is currently the only obstacle standing in its way. Schumer has said he wants to see 60 votes on the bill, a filibuster-proof majority, which many supporters believe are already there, even if all 60 haven’t yet publicly taken a stance.

“Sen. Schumer is working with Sen. Klobuchar and other supporters to gather the needed votes and plans to bring it up for a vote,” a Schumer spokesperson said in a statement.

“There are reasons why it could change. It could be that a bargain is struck, it could be that there’s more pressure,” Feld said of the potential for a vote to be scheduled later in the year. “But the fact is for the antitrust bills, it’s much more a question of, if it doesn’t happen now, it’s not so clear that there’s incentive to make it happen.”

Yen, the Proton CEO, said he felt confident the votes were there for the bill after a recent visit to Washington to meet with lawmakers.

In his conversations, Yen said he saw what he believed was the impact of tech lobbyists who came before him. He said one lawmaker, who he didn’t name, worried the bill would negatively impact retailers in their state. Yen said he pointed out that the bill only applies to companies with over $550 billion in market capitalization, far higher than even Walmart’s market value.

Yen said there’s “a lot of fake information out there that Big Tech has been able to perpetuate because they have $100 million to dump on this.”

He’s optimistic the bill can still see a vote in the lame duck, where he said some lawmakers may see it as a “more convenient” time to vote on such a bill without the looming pressure of the midterm elections.

Cowen’s Gallant agreed there could be a shift in dynamic after the midterms.

“The political calculus for legislation during a lame duck is always a little different,” he said. “It’s conceivable that the major tech antitrust bill still could move during the lame duck. But the odds are against it.”

Gallant said it’s possible Congress ends up voting solely on the Open App Markets Act, a similar but narrower bill focused on mobile app stores like Apple’s and Google’s that gained broader support in the Senate Judiciary Committee than the American Innovation and Choice Online Act.

“It’s a pretty unsatisfying Plan B for the congressional leaders who got AICOA to this point in both houses, but it might be something that people could grit their teeth and live with,” Gallant said.

The best path forward is to pass both bills together, according to Yen, since the broadness of AICOA would make it easier for the law to adapt to future technologies, while the pointed language in the Open App Markets Act would make it less likely for lengthy litigation to delay enforcement.

Supporters of the antitrust bills say failing to pass them risks ceding even more ground in tech regulation to other countries like Europe that have been at the forefront of digital competition enforcement.

“Failing to do so will leave the U.S. out of the game,” said Jennifer Hodges, director of U.S. public policy at Mozilla, which recently endorsed the Klobuchar bill, “and we’ll be playing catch up again like we were with GDPR,” the European data privacy regulation.

Privacy

A bipartisan group of lawmakers across both chambers reached a major agreement on a comprehensive digital privacy bill, marking a significant sign of progress after years of stagnation and disagreement on key parts of such a bill.

The American Data Privacy and Protection Act advanced out of the House Energy and Commerce Committee swiftly after its introduction, but it still lacks support from the top Democrat on the committee of jurisdiction in the Senate, who has raised concerns about the bill’s enforcement mechanisms.

The opposition of Senate Commerce Committee Chair Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., could be “a fatal roadblock,” according to Gallant.

The bill represents a significant move toward compromise on the two key sticking points between Democrats and Republicans: preemption of state laws and private rights of action, or the ability of individuals to sue over violations.

Matt Wood, VP of policy at the nonprofit Free Press, said the privacy bill represents a “legitimate compromise” and even if it’s not perfect, it’s “a true meeting in the middle in ways that we still think are vastly better than the status quo of not having any kind of comprehensive federal rules around this.”

Still, the introduction of the bill just a couple of months before the recess will make it hard to push through before the end of the year.

“It took too long to get where we are today, but it does bode well for Congress to move a privacy bill next year,” Gallant said. “I doubt this is enough of a priority to act in the lame duck but the late stage compromises lay the groundwork for enacting this bill next year.”

Many privacy advocates say the bill is strong, and while they could offer some critiques, they warn to avoid letting perfect be the enemy of good.

Moore, of the tech industry group, shares that sentiment but said full preemption of state laws — one of the areas of compromise in the bill — should remain a high priority.

“The one thing that our members have been really clear on is that if you’re not going to preempt states, don’t bother to do it,” Moore said. “Because all you’re doing is creating a 51st standard to adhere to, instead of creating the one uniform national standard that we need.”

In the absence of a federal privacy bill, Yen of Proton and Hodges of Mozilla both said new competition laws could actually help protect consumer data by opening up more choices for services that safeguard their privacy.

“I actually believe focusing on competition bills will be more effective and will lead to more tangible outcomes sooner for consumers,” Yen said. He pointed to the 30% revenue cut he pays to Apple and Google for subscriptions he sells through their mobile app stores. Yen said that model incentivizes companies like Meta’s Facebook to be ad-supported to avoid giving away such a share of their revenue.

Google and Apple have said the revenue they take helps fund the service of their app stores and keeps them secure.

“They are actually creating a system that is incentivizing surveillance capitalism at the expense of other business models that are better for user privacy,” Yen said. “So if the 30%, were to go away, if you would have free choice of payment methods to use, you would find that entrepreneurs would probably prefer subscription services versus ad-based models.”

Net Neutrality

Several experts interviewed for this article said the Biden administration and Congress moved too slowly on the nomination and confirmation of Gigi Sohn as Federal Communications Commissioner.

Biden waited until October 2021 to nominate Sohn alongside then-Acting Chair Jessica Rosenworcel to take on the full-time leadership role. While Rosenworcel’s confirmation was swift, Sohn’s has been stuck in limbo after two hearings on her nomination and Republican opposition to her past statements against Fox News. And when Sen. Ben Ray Lujan, D-N.M., had a stroke, the Senate Commerce Committee was left without the votes to advance Sohn’s nomination for longer than expected.

“I think her nomination is a case study and how not to run a nomination for an agency,” Gallant said. “I think the White House has made multiple mistakes in moving the ball forward at the FCC.”

The delay means the FCC has not been able to begin the process of reinstating net neutrality rules, which were undone under former President Donald Trump’s FCC Chair Ajit Pai. Net neutrality is the concept that internet service providers should not discriminate, block or throttle different web traffic. The concept was enshrined under the Obama administration by reclassifying internet service providers under Title II of the Communications Act, which categorized them as common carriers.

ISPs like AT&T, Verizon and Comcast, owner of CNBC parent NBCUniversal, have opposed such reclassification in large part for fear it could lead to price regulations down the road. Gallant said it’s likely the ISPs would still prefer a deadlocked commission to prevent reclassification again, but believes investors no longer view it “as much of a risk to the business models.”

“We had a natural experiment on this question already,” he said. “Under Obama, we had net neutrality rules. And under Trump we didn’t. And carrier behavior did not change in either. So net neutrality rules don’t matter to the business models. Title II could be viewed as a step toward some type of price regulation by the FCC. But I think the ISPs have largely neutralized that through their commitment to low price broadband for low income households.”

But some net neutrality advocates would argue the looming threat of reclassification and enforcement of a net neutrality law in California have helped keep the worst potential behavior at bay.

“I think the situation remains the same in terms of the market power that ISPs have, and in their ability to leverage that to slow, block or prioritize content there,” said Hodges of Mozilla, which sued the FCC over its rollback of net neutrality rules under Pai. “We certainly are of the view that net neutrality remains an issue that needs to be addressed at the federal level, whether FCC, or Congress, right, but in a lasting way.”

A group of Democratic senators recently introduced a bill that would enshrine net neutrality into law, but FCC rulemaking would likely be a much more expeditious path to the reinstatement of the policy.

For Sohn, who was a Mozilla Fellow and Public Knowledge co-founder, “it ain’t over till it’s over,” Feld said.

“I have seen on a number of occasions where people assumed that nominations were dead, and then in a lame duck session, they just crank ’em out,” he said. “I think that it is very possible, for example, that especially if the Senate is going to change hands that we might see, Schumer prioritize getting a bunch of these nominees through on the theory that if Republicans take over they’re not going to approve any Biden nominees.”

Though several of these tech policy issues have failed to advance as quickly as their champions have hoped, Wood of Free Press recalled that such a setback is far from unheard of.

He said the Telecom Act of 1996, which passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, took several sessions of Congress to craft and push through.

“It was a maybe a decade-long arc, give or take a year or two,” Wood said. “Don’t misunderstand, I would share people’s frustration if they’re like, ‘the technology is moving at a faster pace than that, can we do better?’ And yet, I don’t think this is such a new phenomenon.”

Disclosure: Comcast is the owner of CNBC parent company NBCUniversal.

This post has been syndicated from a third-party source. View the original article here.