AI reveals melting temperature of all known earthly minerals

Melting temperatures are often measured after carefully calibrating crystal structures or plotting the thermodynamic free energy curves when a material melts, creating a phase change from a solid to a liquid. But when high-temperature materials exceed 2,000 or 3,000 degrees, finding an experimental chamber to do the measurements can be a challenge. And sometimes, rocks have complex mixtures of minerals not much larger than a grain of sand—so getting enough samples of a single mineral can also present a challenge. This is where AI comes in.

“We employ machine learning methods to fill this gap by building a rapid and accurate mapping from chemical formula to melting temperature,” Qi-Jun Hong, one of the scientists involved in this research, said in a media statement. “The model we have developed will facilitate large-scale data analysis involving melting temperature in a wide range of areas. These include the discovery of new high-temperature materials, the design of novel extractive metallurgy processes, the modelling of mineral formation, the evolution of earth over geological time, and the prediction of exoplanet structure.”

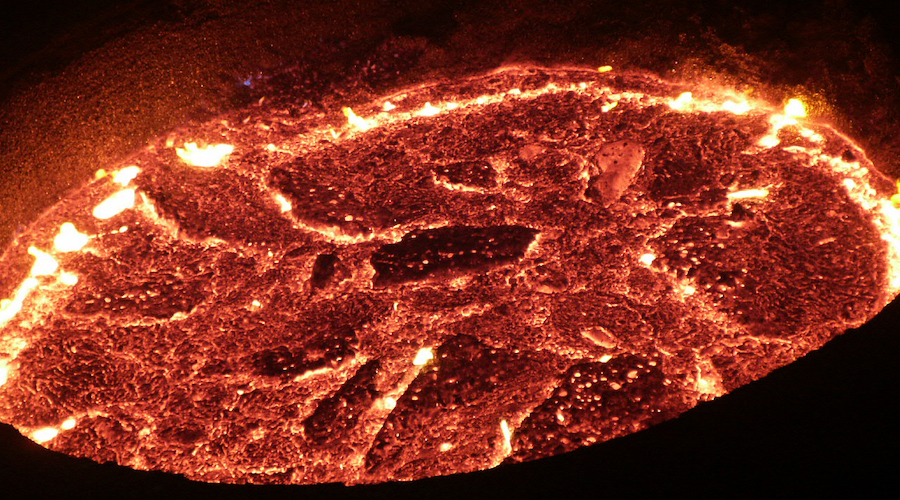

Hong’s approach allows melting temperatures to be computed in milliseconds for any compound or chemical formula input. To do so, the research team built a model from an architecture of neural networks and trained their machine learning program on a custom-curated database encompassing 9,375 materials, out of which 982 compounds have melting temperatures higher than a scorching 3100 degrees Fahrenheit. Materials at this temperature glow white-hot.

Two-way research

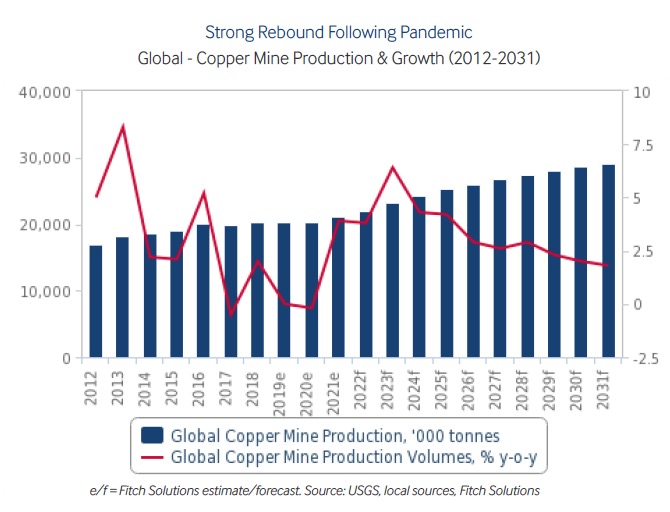

The methodology is being used to explore two lines of research: 1) predicting the melting temperatures of nearly 5,000 minerals and 2) finding new materials that have extremely high melting temperatures above 5000 degrees Fahrenheit.

For the minerals project, Hong’s team was able to predict melting temperatures and correlate these with the known major geological epochs of earth’s history.

These AI-garnered melting temperatures were applied to minerals made since the formation of the earth about 4.5 billion years ago. The oldest minerals originate directly from stars or interstellar and solar nebula condensates predating earth’s formation 4.5 billion years ago. These are the most refractory, with melting temperatures around 2600 F.

For the most part, there was a gradual decrease in the calculated melting temperatures of minerals identified on earth in more recent times, with two major exceptions.

“The gradual overall decrease in the melting temperature of minerals formed during earth’s history is interrupted with two anomalies, which are distinctly pronounced in average and medium melting temperatures using 250 or 500 million years ago binning,” Alexandra Navrotsky, co-author of the study that presents these findings, said.

The first anomaly in earth’s early history came from a dramatic temperature spike caused by a time of major meteor strikes, which possibly led to the formation of the moon.

“The spike at 3.750 billion years ago correlates to the proposed timing of late-heavy bombardment, hypothesized exclusively from dating of lunar samples and currently debated,” Navrotsky said.

Formation of water-containing minerals

The team also noticed a large temperature dip in the melting temperatures of minerals around 1.75 billion years ago, which is related to the first known occurrences of a large number of hydrous (water-containing) minerals and correlates with the Huronian glaciation, the longest ice age thought to be the first time our planet was completely covered in ice.

With their machine learning program trained to successfully replicate mineral melting in earth’s early history, next, the team turned their attention to finding new materials that have extremely high melting temperatures.

Dozens of new materials were identified and computationally predicted to have extremely high melting temperatures above 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit, more than half the temperature of the sun’s surface.

The team made the model simple and reliable enough so that any user can obtain the melting temperature within seconds for any compound based only on its chemical formula.

“To use the model, a user needs to visit the webpage and input the chemical compositions of the material of interest,” said Hong. “The model will respond with a predicted melting temperature in seconds, as well as the actual melting temperatures of the nearest neighbours (i.e., the most similar materials) in the database. Thus, this model serves as not only a predictive model but a handbook of melting temperature as well.”

This post has been syndicated from a third-party source. View the original article here.