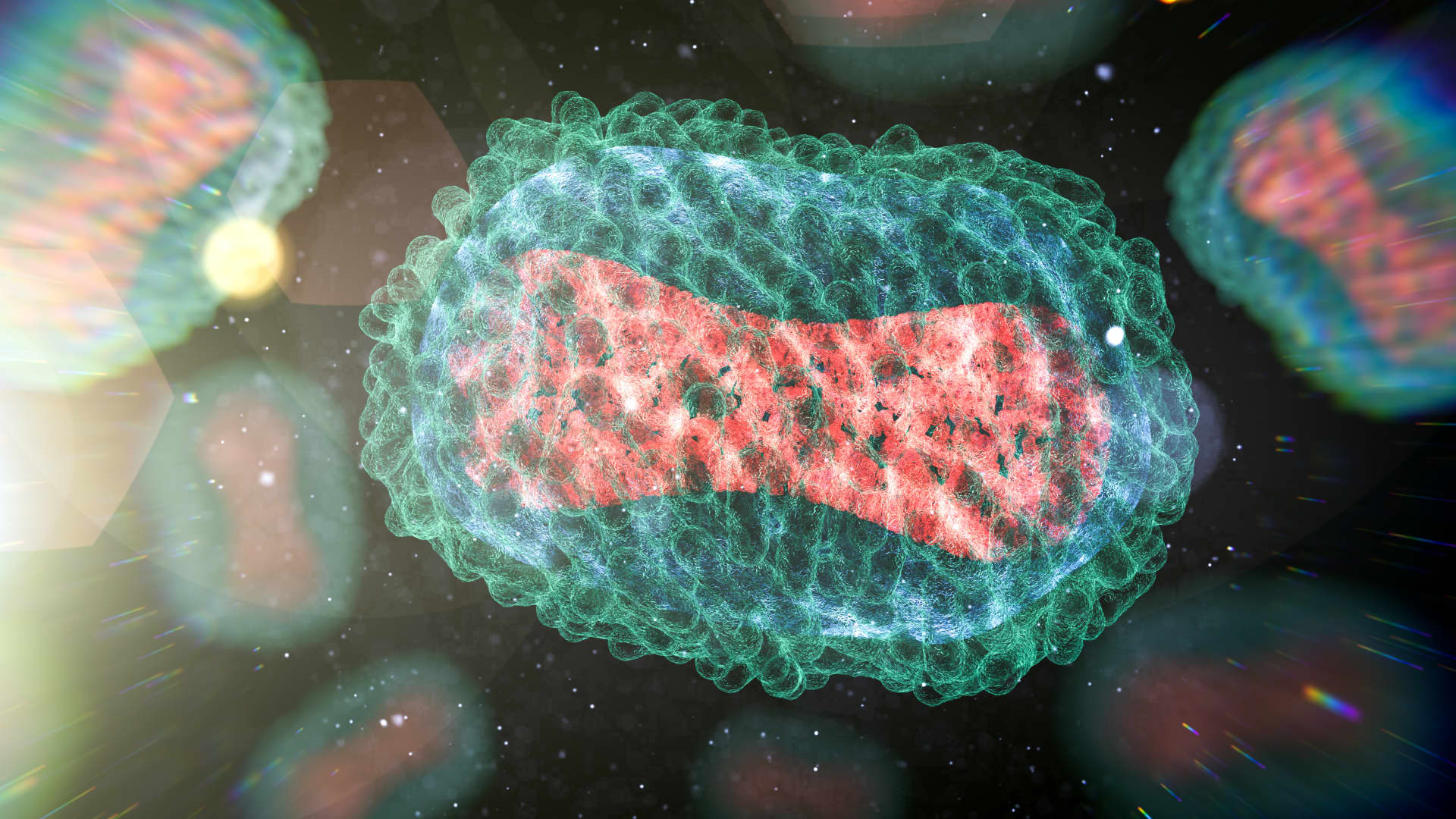

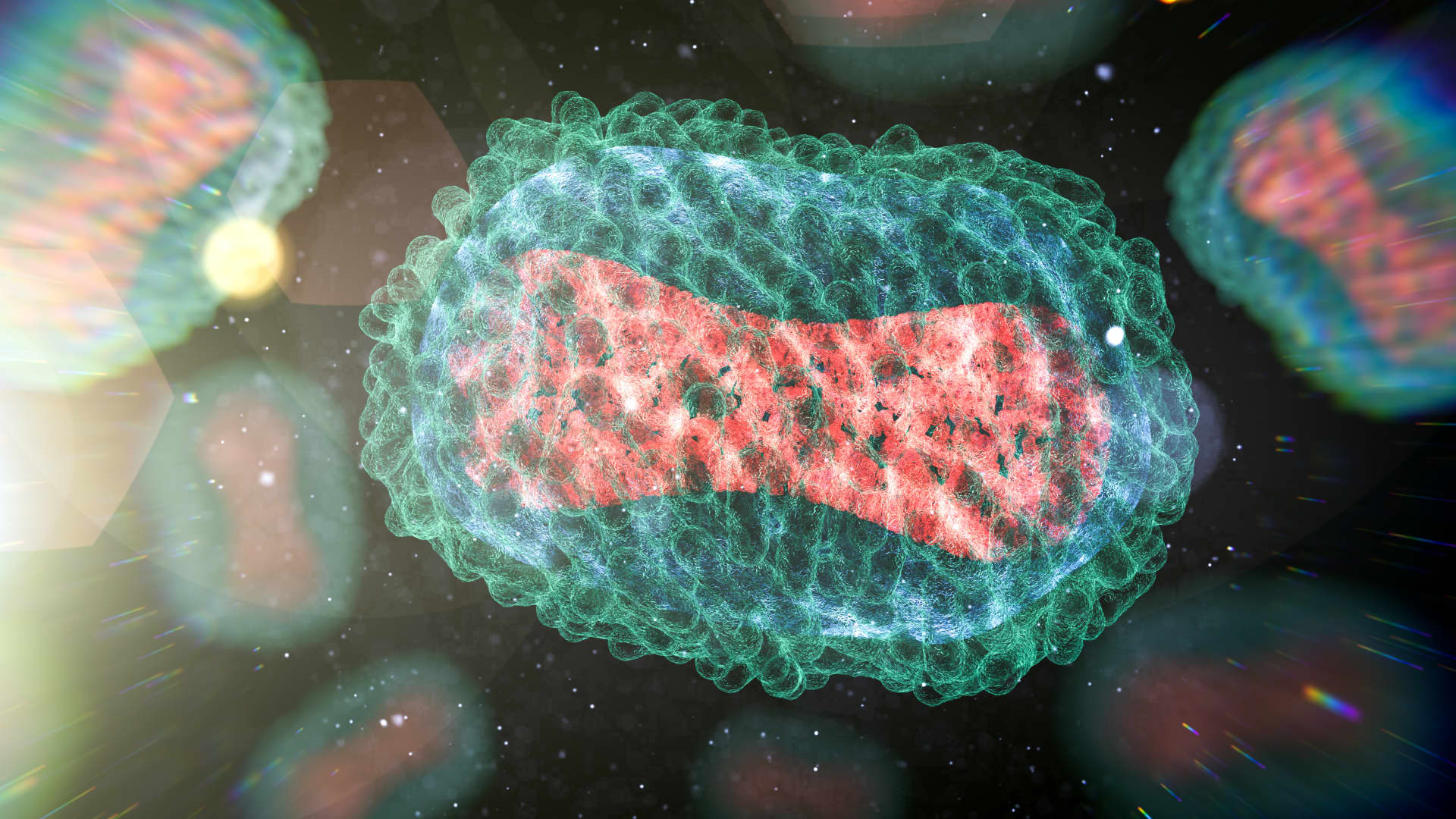

A dog in France has monkeypox, worrying scientists that we won’t be able to eradicate the virus if it spreads to more animals

In 2003, 47 people across six Midwestern states caught monkeypox from pet prairie dogs that were infected after they were housed with rodents imported from Ghana, Africa.

Today’s outbreak, which has already infected more than 14,100 people in the U.S. and more than 41,000 across the globe, is spreading mostly through close human contact among gay and bisexual men. But scientists reported the first presumed human-to-pet transmission in a dog in France this month, prompting U.S. and global health officials to step up warnings to ensure the virus doesn’t spread to other pets and animals.

The recommendation stems from concerns that monkeypox could spill into wildlife or rodent populations as the human outbreak grows, allowing the virus to pass back-and-forth between humans and animals and giving the virus a permanent foothold in countries where it hasn’t historically circulated.

Prior to the global outbreak this year, monkeypox spread primarily in remote parts of West and Central Africa where people caught the virus after exposure to infected animals. The 2003 outbreak, which was contained, was the first documented case of humans catching the virus outside Africa.

The current global outbreak differs dramatically from past patterns of transmission. Monkeypox is now spreading almost entirely through close physical contact between people in major urban areas in the U.S., European nations and Brazil.

But the first presumed case of people infecting an animal in the current outbreak was reported in France this month. A pet dog tested positive for the virus after a couple in Paris fell ill with monkeypox and shared their bed with the animal.

WHO officials have said a single incident of a pet catching the virus is not surprising or a cause for major concern, but there is a risk that monkeypox could start circulating in animals if people don’t know they can infect other species.

If monkeypox becomes established in animal populations outside Africa, the virus would have more opportunities to mutate, which carries the risk of higher transmissibility and severity. Animals could then potentially give the virus to people, increasing the risk of future outbreaks.

“What we don’t want to see happen is disease moving from one species to the next and then remaining in that species,” said Dr. Mike Ryan, director of the WHO’s health emergencies program, said during a press conference in Geneva last week. “It’s through that process of one animal affecting the next and the next and the next that you see rapid evolution of the virus.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not received any reports of pets infected with monkeypox in the U.S., said Kristen Nordlund, an agency spokesperson. But the virus can spread from people to animals or from animals to people, according to the CDC.

“While we are still learning which species of animals can get monkeypox, we should assume any mammal can be infected with monkeypox virus,” Nordlund said. “We do not know if reptiles, amphibians, or birds can get monkeypox, but it is unlikely since these animals have not been found to be infected with viruses in the same family as monkeypox.”

Dr. Rosamund Lewis, the WHO’s lead monkeypox expert, said it’s important to dispose of potentially contaminated waste properly to avoid the risk of rodents and other animals becoming infected when they rummage through garbage.

“While these have been hypothetical risks all along, we believe that they are important enough that people should have information on how to protect their pets, as well as how to manage their waste, so that animals in general are not exposed to the monkeypox virus,” Lewis said.

Ryan said that while vigilance is important, animals and pets do not represent a risk to people at the current time.

“It’s important that we don’t allow these viruses to establish themselves in other animal populations,” Ryan said. “Single exposures or single infections in particular animals is not unexpected.”

Rodents in Africa

Although scientists have done some research on monkeypox in Africa, where it’s historically circulated, their work was limited due to a lack of funding. So scientists don’t know how many different species of animals can carry the virus and transmit it to humans.

Scientists have only isolated monkeypox from wild animals a handful of times in Africa over the past 40 years. They included rope squirrels, target rats and giant pouched rats in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as two types of monkeys in Cote d’Ivoire. Rodents, not monkeys, are thought to be the host animal population in Africa, though the precise animal reservoir is unknown.

Public health officials don’t know whether the types of animals in close proximity to people in urban settings in the U.S. — racoons, mice and rats — can pick up and transmit the virus. Some types of mice and rats can get monkeypox but not all species are susceptible, according to the CDC.

“We know this is a virus that’s transmitted from rodents in West Africa,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, an infectious disease expert at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. “Could rats or other rodents in urban environments mean that it gains a foothold there and it also becomes more of a permanent fixture — we don’t want that to happen,” he said.

The CDC recommends that people who have monkeypox avoid contact with animals — pets, livestock, domestic animas and wildlife. If a pet becomes sick within 21 days of contact with someone who has monkeypox, the animal should be evaluated by a veterinarian.

Waste contaminated with monkeypox should go into in a lined, dedicated trash can and shouldn’t be left outside because wildlife could potentially become exposed the virus, according to CDC.

U.S. outbreak in 2003

In the 2003 outbreak, the CDC was able to quickly administer vaccines and quarantine patients before the virus could spread farther. There were no cases of monkeypox spreading between people. The CDC then banned the importation of rodents from Africa.

Containing the 2003 outbreak took 10,000 hours of work to trace the virus back to Gambian rats and other rodents imported from Ghana to an animal distributor in Texas, according to Marguerite Pappaioanou, a former CDC official who worked on the outbreak.

The Food and Drug Administration banned the importation of all African rodents in the wake of the 2003 outbreak. The agency also prohibited the interstate distribution of prairie dogs and their release into the wild over concerns monkeypox could become established in wildlife populations.

The U.S. Georgical Survey and Department of Agriculture subsequently trapped 200 wild animals in Wisconsin at sites close to where humans contracted monkeypox from pet prairie dogs. They did not find any evidence that the virus had spread into wild animals, and the FDA lifted the ban on distributing prairie dogs between states. It’s still illegal to import rodents from Africa.

Wastewater worries

Scientists in California detected monkeypox DNA in sewage samples this summer. New York is also conducting wastewater surveillance for the virus, according to the state health department, though results have not been publicly released yet. The wastewater findings in California have raised concern among some health experts that the virus could infect rodents through the sewage.

“There is the risk because of the widespread nature of infections and the fact that it’s sewage and wastewater,” said Dr. James Lawler, an infectious disease expert at Global Center for Health Security at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. “That’s a concern, about getting into an animal population and having a zoonotic risk reservoir and honestly, if that’s the case that I think it’s game over for us.”

But it’s not clear if live virus is present in wastewater. The study measured monkeypox DNA in sewage samples, not whether the virus was still infectious, according to Marlene Wolfe, a scientist at Emory University who is working on the project.

Wastewater is treated in most urban areas so the probability of the virus surviving and replicating in such an environment is low, according to Amira Roess, a former official with the CDC’s Epidemiological Intelligence Service. Roess said garbage that contains contaminated materials such as bedsheets or towels likely poses a higher risk than wastewater.

“There are wildlife species that rummage in your garbage and then they’re more likely to pick up virus that is able to replicate. “There’s a lot of ifs, but it happens,” said Roess, who is now a professor of epidemiology at George Mason University.

Low probability

Several steps would have to take place for the monkeypox virus to spill over from humans into animals and then spill back into people causing another outbreak, according to Richard Reithinger, an epidemiologist at RTI International.

The virus would have to circulate in an animal population with a wide geographic distribution, but not cause so much mortality in the species that the train of transmission is snuffed out, Reithinger said. Humans would also need to have some level of regular contact with animals.

“Each step has a certain probability. Once once you kind of add up all the probabilities of these steps, the probability actually becomes quite low,” Reithinger said.

It’s also possible that monkeypox might be transmitting more efficiently among people in the current outbreak due to some sort of viral mutation, Roess said. If the virus has adapted to humans, it could be more difficult for people to give the disease to animals, she added. It also depends on what kind animal comes into contact with the virus, according to Pappaioanou.

“All animals are not susceptible. We don’t even know which ones are,” said Pappaioanou, who is now an affiliate professor at the University of Washington.

Better surveillance needed

Although the risk of the virus becoming entrenched in a U.S. animal population and causing future human outbreaks is low, the U.S. needs a more robust surveillance system to prepare for such a possibility, according to Pappaioanou and Roess. There are major gaps in the ability of public health agencies to monitor animal populations for infectious diseases, the former CDC officials said.

“It’s a very big gap. We don’t have a good surveillance system for humans,” Roess said. “For wildlife, it depends on who is interested in what pathogen and if they’re able to convince someone to fund surveillance. A lot of our surveillance is just really sporadic”

Livestock such as cows, sheep and poultry are monitored by the Department of Agriculture, Pappaioanou said. But wildlife surveillance is underfunded and it takes a tremendous amount of work to monitor these animals for infectious disease, she said There’s no government agency that overseas the health of dogs and cats, she said. Local health departments may monitor rodents and have population control programs but this also requires funding and significant staffing, she added.

“More and more people around the world are moving to cities,” Pappaioanou said. “What would it mean in a highly urbanized city to have a reservoir of infection? We don’t know the answer.”

This post has been syndicated from a third-party source. View the original article here.